Post-Earthquake Motions

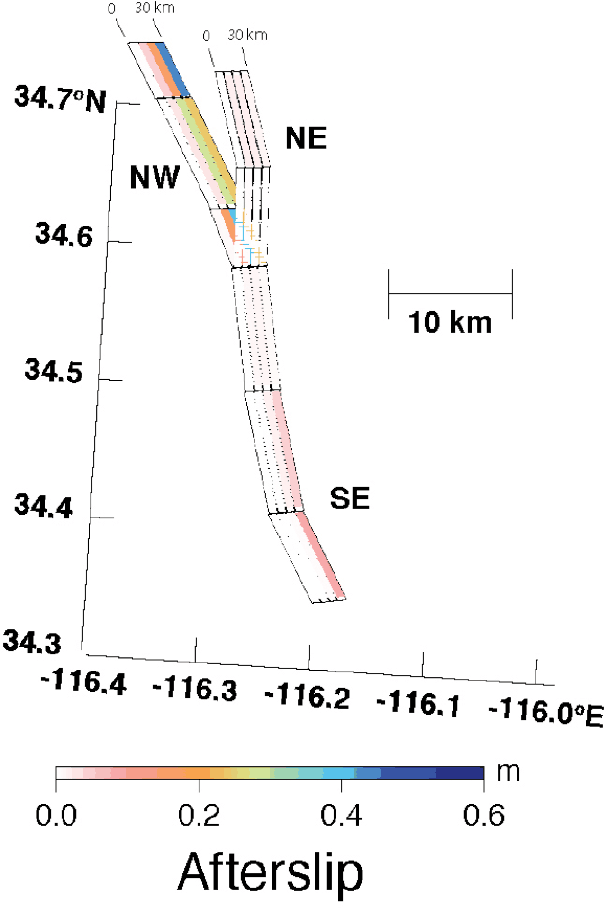

After a large earthquake, the crust does not stop moving. Earthquakes such as the 1994 M6.7 Northridge, California, or 1989 M6.9 Loma Prieta, California, earthquakes are followed by hundreds of aftershocks, some of them damaging. Many aftershocks occur on the causative fault or its extension into the deeper earth. The slip associated with these aftershocks is termed afterslip. It may occur in the form of ordinary earthquakes or as slow slip that is not felt.

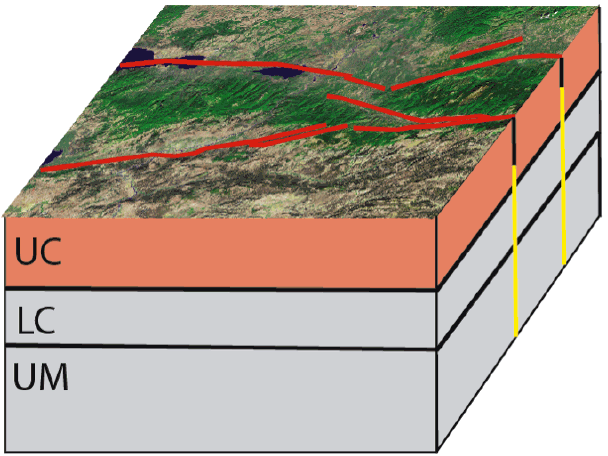

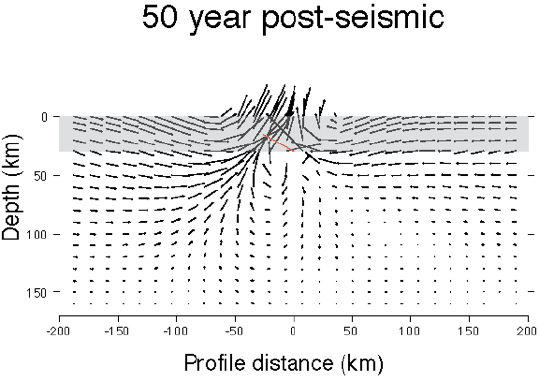

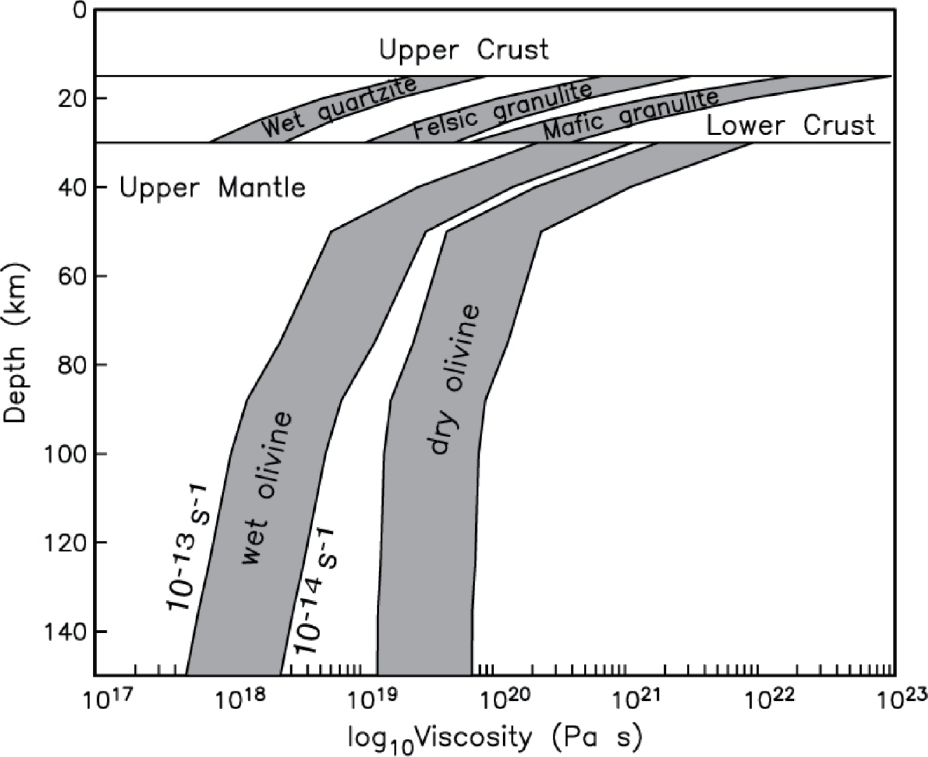

Another process that occurs after an earthquake is relaxation of the ductile rock that underlies the uppermost crust. While most earthquakes occur in the uppermost crust because frictional resistance is high (and hence stress builds up over long periods of time), few occur in the deeper crust or underlying mantle because the rock temperature is too high to permit accumulation of stress. Instead, stress is accommodated by flow of the rock. The depth where the transition from brittle friction to ductile flow is called the brittle-ductile transition, and it generally coincides with the maximum depth of earthquakes, typically 10-20 km (Implications of the Depth of Seismicity for the Rupture Extent of Future Earthquakes in the San Francisco Bay Area).

Understanding these processes is important for estimating how faults interact with one another through stress transfer, which can change the seismic hazard for years after an earthquake. Part of this understanding comes from better knowledge of the temperature and composition of rocks deep beneath earth’s surface.

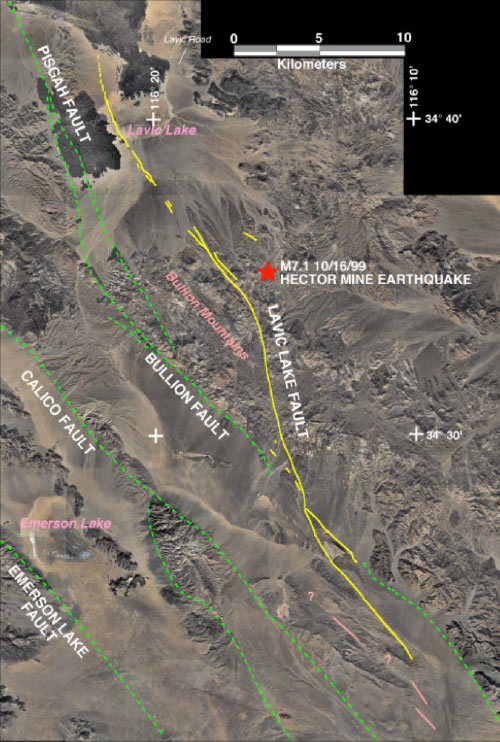

Case Study: M7.1 October 16, 1999 Hector Mine, California, Earthquake

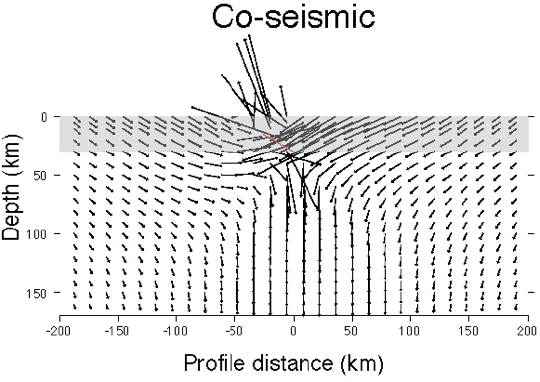

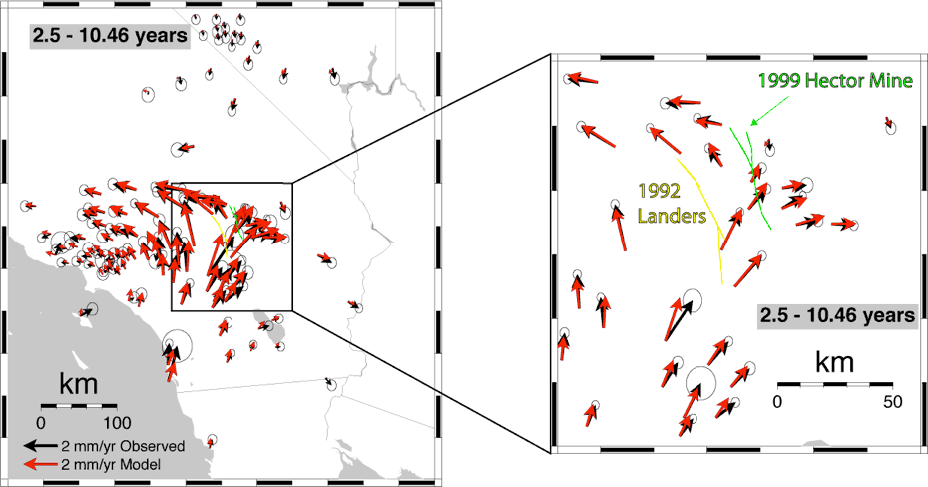

The Hector Mine earthquake occurred in the central Mojave Desert and produced several meters of slip along faults of total length ~40 km. It was well-recorded by continuous GPS sites of the SCIGN Network that were already in place in the aftermath of the 1992 M7.3 Landers earthquake, as well as new continuous and survey-mode GPS that were installed in the region by scientists soon after the Hector Mine quake.

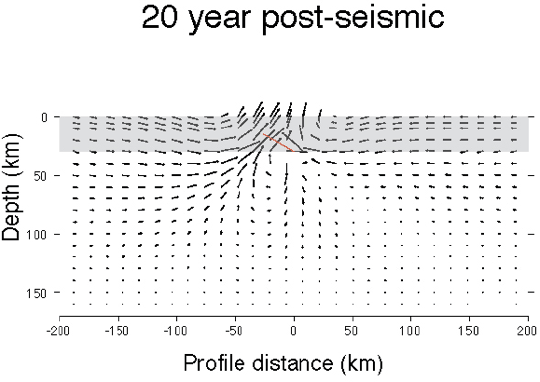

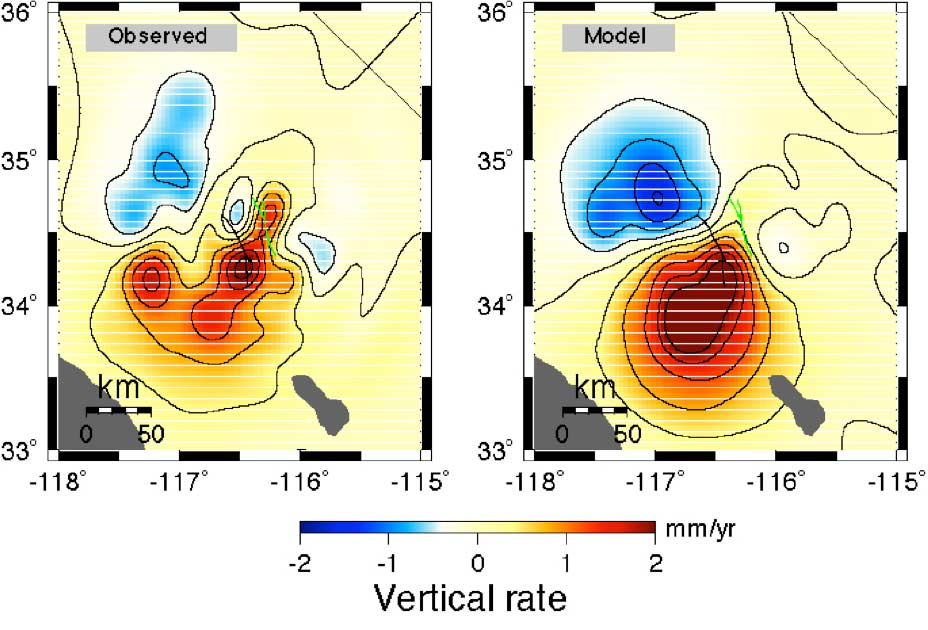

Both afterslip on thin zones below the causative fault and relaxation of the flowing lower crust and mantle occurred in the months and years after the Hector Mine earthquake.

2.5 years after the 1999 Hector Mine quake quake, almost all regional motions above the ‘background’ tectonic motions are due to flow of rock in the lower crust and upper mantle. This motion can be tracked unambiguously up to 10.46 years after the 1999 Hector Mine quake, at which time the M7.2 April 4, 2010 El Mayor-Cucapah earthquake changed the regional flow pattern. A model of the flow based on the laboratory behavior of wet olivine and mafic granulite compositions (Thatcher and Pollitz, 2008) agrees well with observed motions.

References

- Pollitz, F.F., in preparation (2014). Post-earthquake relaxation evidence for laterally variable viscoelastic structure and elevated water concentration in the southwestern California mantle.

- Thatcher, W. and Pollitz, F.F. (2008). Temporal evolution of continental lithospheric strength in actively deforming regions, GSA Today, 18, 4-11.

Jump to Navigation

Jump to Navigation