Ground Movements

Measureable permanent ground displacements are produced by shallow earthquakes of magnitude 5 and greater. These displacements are used by seismologists to understand the earthquake source in detail, such as the amount of slip and the type of underground fault which ruptured. This information has been traditionally used to analyze earthquakes long after they occur, but recent work in Earthquake Early Warning may allow such geodetic measurements to be exploited in real time in order to help provide warning of earthquake shaking while the earthquake is in progress.

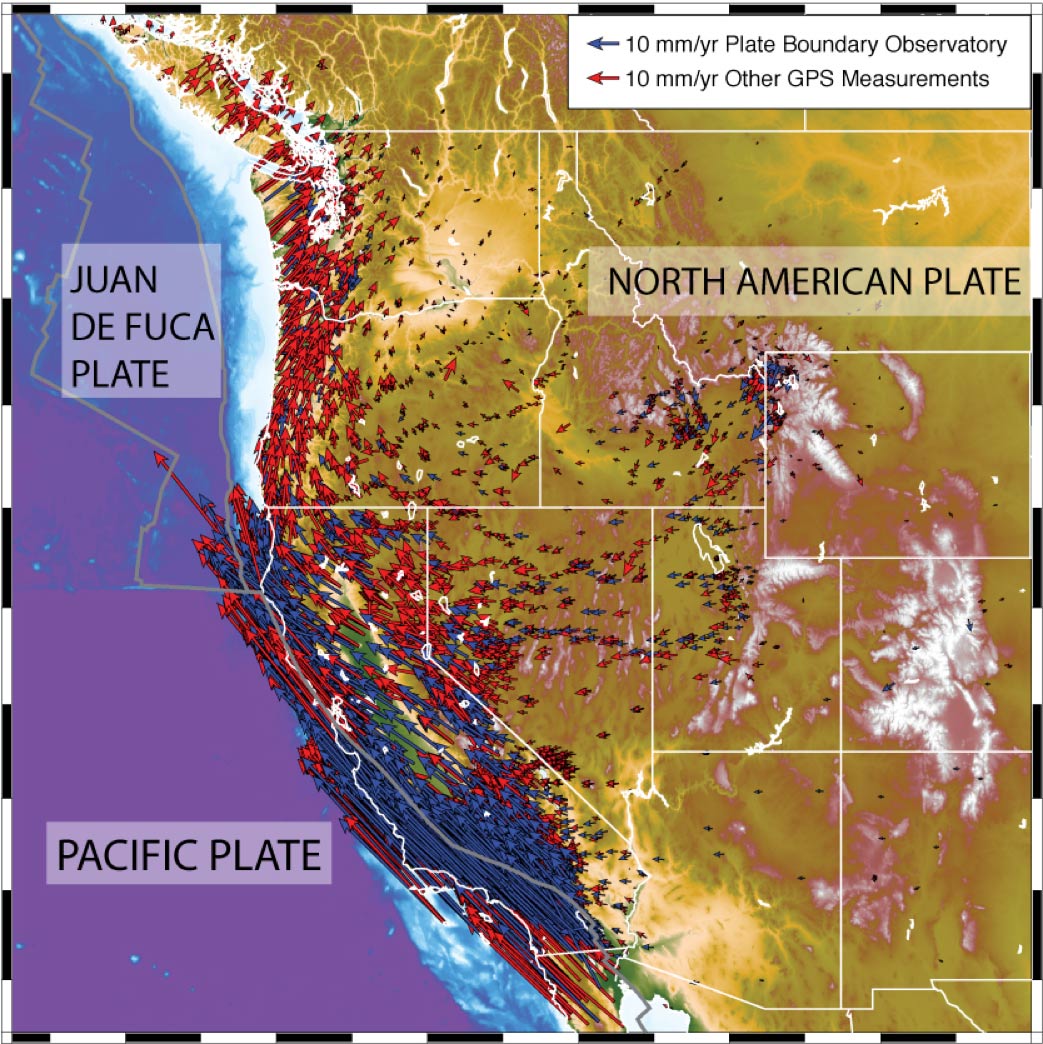

Steady background motions of Earth’s crust occur as a result of tectonic plate motions. As the Pacific plate slides past the North American plate, they become stuck at the boundary zone between them, which typically has many faults. If these faults are stuck, then there may be no motion across them for tens to hundreds of years, during which time they build up stress until an earthquake occurs. The earthquake relieves the stress, the fault is stuck again, and the cycle of stress buildup and release begins anew. This process has been documented on the Hayward fault and San Andreas fault for the past few thousand years using geologic investigations.

Many faults in the San Francisco Bay area are not completely stuck, but instead they undergo fault creep, steady motions along the fault. If these motions proceed as rapidly as the plates slide past each other, then the fault is essentially ‘unstuck’ and no stress builds up. This is the case for portions of the Hayward fault, Calaveras fault, and San Andreas fault.

Measureable motions above the ‘background’ often occur days, months, or even years after an earthquake occurs, even though the causative faults are stuck. This usually happens after magnitude > 7 earthquakes. Such motions continued for several years following the 1999 M7.1 Hector Mine earthquake in the Mojave Desert, California. Such large earthquake impart large stresses into the Earth’s lower crust and mantle, the layer between the crust and the core. The lower crust and mantle have higher temperature than the upper crust (the upper ~15 km), and minerals like quartz will flow at these higher temperatures. As a result, stresses that lead to earthquakes tend to be concentrated in the continental upper crust, but the gradual dissipation of these stresses in the ductile layer will lead to continued crustal motions for years after a large earthquake.

Some ‘earthquakes’ occur without shaking. Scientists often refer to these events as slow earthquakes. Many slow earthquakes occur along the Cascadia subduction zone, where the Juan de fuca plate is plunging beneath the North American plate . Many also occur in the San Francisco Bay area, specifically along the creeping central San Andreas fault.

Surface Motions

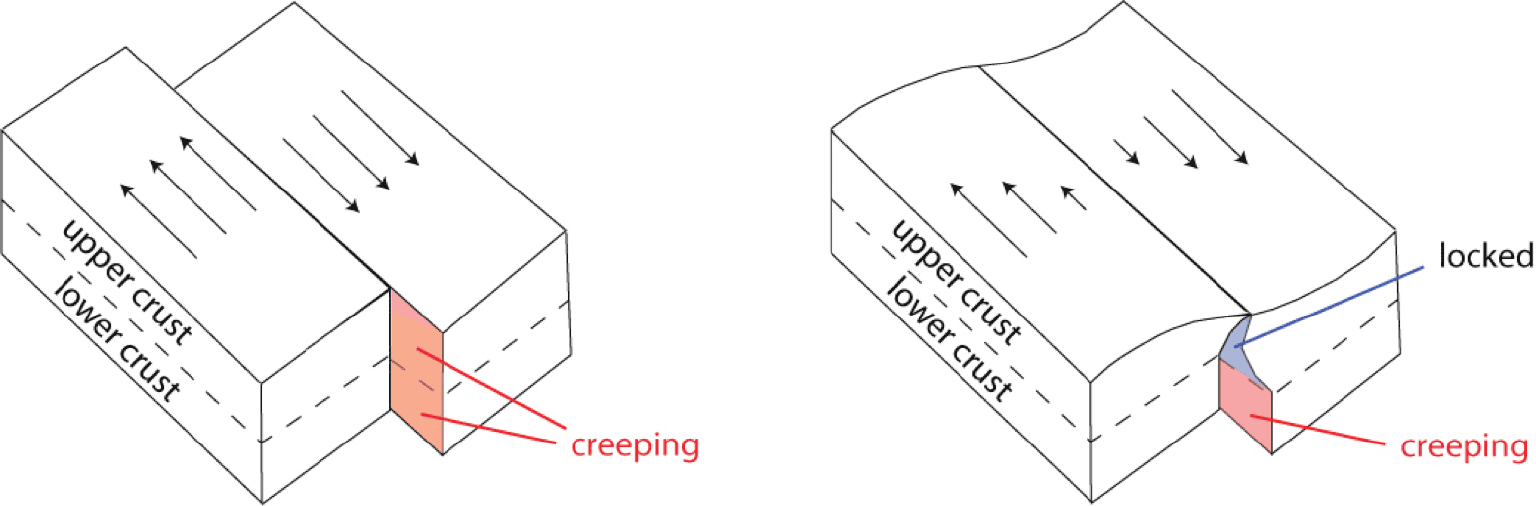

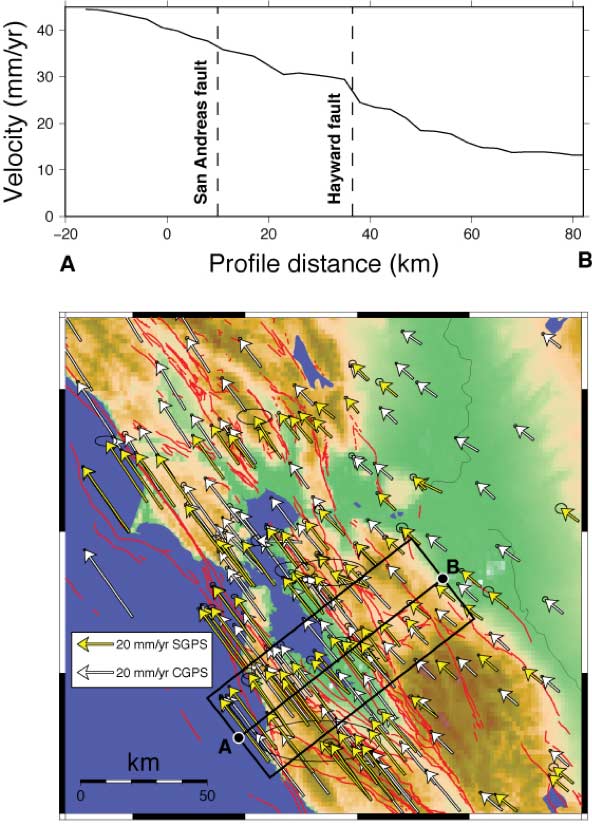

Faults are thought to be creeping at depth in the lower crust, where the lack of frictional resistance at the prevailing high temperatures allows steady fault slip and no buildup of stress. Faults may also be creeping at shallower depth in the upper crust (left figure), leading to block-like motions and sharp changes in surface velocity across the fault. Faults are usually locked in the upper crust (right figure), leading to a gradual change in surface velocity across the fault and bending of the upper crust. This bending produces stress buildup that eventually leads to earthquakes.

The horizontal velocity field in the San Francisco Bay area is constrained by continuous GPS (CGPS) and survey-mode GPS (SGPS) measurements. These velocities are almost parallel to the regional faults and decrease from west to east as one approaches the interior of the North American plate. While a gradual transition across the San Andreas Fault indicates that it is locked, the abrupt transition across the southern Hayward fault indicates that it is creeping. This is confirmed by creepmeter measurements across the Hayward fault. creepmeter measurements across the Hayward fault.

Jump to Navigation

Jump to Navigation