What is GPS?

GPS stands for Global Positioning System. The Global Positioning System is a group of satellites orbiting the Earth twice a day at an altitude of about 20,000 kilometers (12,000 miles).

GPS was designed by the military to locate tanks, planes and ships and has been adopted by the public for navigation and scientific applications. Using a GPS device or smart phone, you can pinpoint your location anywhere on Earth. All you need is a clear view of the sky (this could be a problem in a dense forest or indoors).

How Does it Work?

GPS satellites continuously broadcast messages on 2 radio frequencies. These messages contain a very accurate time signal, a rough estimate of the satellite's position in space, and a set of coded information that a GPS receiver can decipher.We want to know our latitude, longitude, and elevation. The receiver uses its internal clock and the coded information from each GPS satellite to determine the time it took the signals to reach the receiver. Since the signals travel at the speed of light, the receiver can calculate the distance to each satellite.

Once the receiver knows the distances to at least 4 satellites, and their positions, it can determine its clock correction and position on the Earth.

Accuracy

Using a smart phone, you can determine your location to within 10 meters (about 30 feet) or less. That accuracy is fine for navigation. But since the motion across faults, such as the San Andreas, is usually less than 5 centimeters (2 inches) per year, the USGS has to use special techniques to achieve much higher accuracy.

How Does USGS Use GPS to Measure Fault Motion?

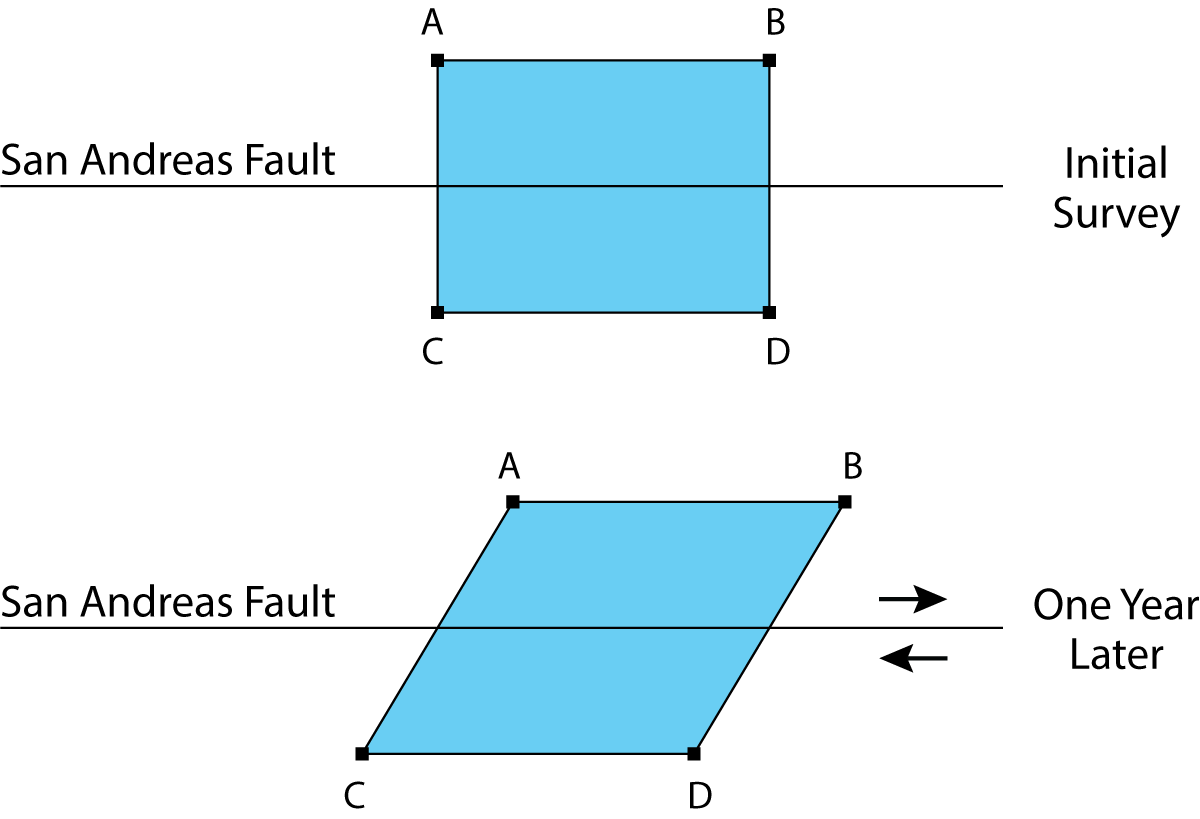

We want to know how stations near active faults move relative to each other. When we occupy several stations at the same time, and all stations observe the same satellites, the relative positions of all the stations can be determined very precisely. Often we are able to determine the distances between stations, even over distances up to several 100 miles, to better than 5 millimeters (about a 1/4 of an inch).

Months or years later we occupy the same stations again. By determining how the stations have moved, we calculate how much strain is accumulating and which faults are slipping.

Where Do We Work?

The USGS uses GPS to measure crustal deformation all over the United States. However most of the work is concentrated in the western states where most earthquakes occur and where rates of crustal deformation are high. These web pages contain maps and data for individual “campaigns” or sets of stations that we monitor.

Jump to Navigation

Jump to Navigation