Earthquake Nucleation Studies Using a Biaxial Earthquake Apparatus

A key question in earthquake science is: “How do earthquakes begin?” Laboratory experiments, theoretical arguments, and numerical models all indicate that earthquakes begin relatively slowly in a process referred to as earthquake nucleation.

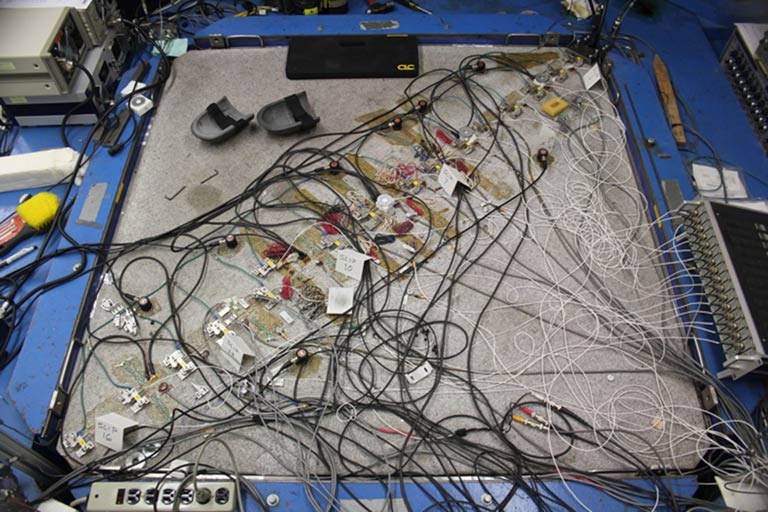

We studied the initiation of stick-slip on a simulated fault, which is cut through a large laboratory specimen as an analogue for earthquake nucleation. This research was conducted on a large-scale biaxial earthquake apparatus. This unique facility is the largest of its kind in the world. Made in the 1970s by Jim Dieterich and Quentin Gorton, the apparatus accommodates samples 1.5 m by 1.5 m by 0.4 m in size and can apply over a million pounds of force to a 2 m long fault cut diagonally through the Sierra White granite sample.

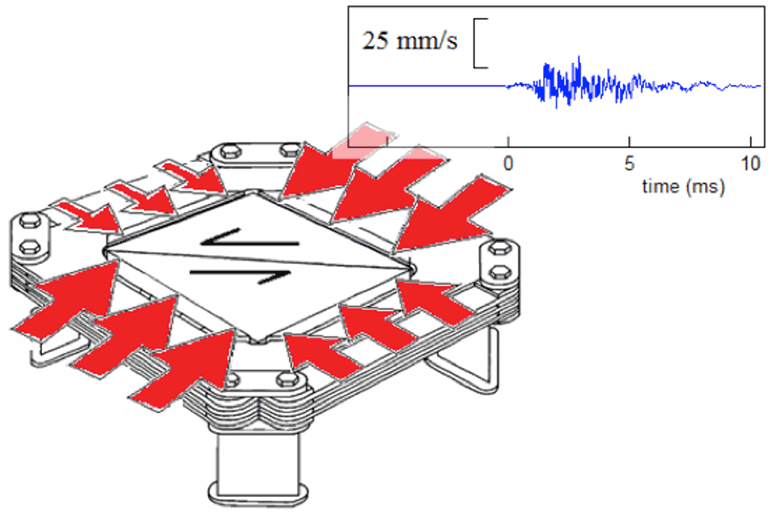

Since its construction in the 1970s, the instrumentation on the laboratory sample has been significantly improved, thanks to Brian Kilgore. The 2-meter-long fault is instrumented with arrays of high speed slip sensors and strain gages that are used to measure local fault slip and stress changes at many locations. In this large-scale experiment, one part of the fault may begin to slip while another part remains locked. Recently, Greg McLaskey has installed an array of 15 piezoelectric sensors on the sample. These sensors are the laboratory equivalent of a seismic network and record the ground motions due to seismic waves radiated from the fault when it ruptures in a simulated earthquake. These sensors have also allowed us to detect tiny foreshocks and aftershocks that occur on the fault when it slips slowly during nucleation and afterslip.

Jump to Navigation

Jump to Navigation