Rate- and State-Dependent Friction

Jump to Navigation

Jump to Navigation

The coefficient of friction of rocks and other geologic materials is an important physical property that is used for the modeling of active faults and earthquake processes. However, rock friction depends on many things such as the sliding speed and sliding history. In fact, because rock surfaces are rough, even on a microscopic scale, not all parts of the surfaces are in contact across the fault plane at the same time. High spots, known as “asperities” on one surface will touch high spots on the other surface. These connecting asperities are points of high stress and can fracture or creep with time. As the rocks slide past one another, the asperity contacts will grow, coalesce, and evolve. These effects of sliding history are described by empirical equations known as “rate- and state-dependent constitutive laws”. How are the variables in the constitutive laws determined?

Three rectangular pieces of granite are sandwiched together between steel plattens. The central rock slides vertically past the two smaller rocks. Shear displacement is measured by the transducer in the foreground. Other transducers measure the shear and normal stresses on the sliding surfaces. Rate-dependent parameters are determined by sliding the rocks at different speeds and observing how the coefficient of friction changes. Certain rocks and minerals become stronger with faster sliding rates. This promotes stable sliding (i.e., no earthquakes). Other materials become weaker, a trait associated with unstable sliding. Also noted during experiments at different sliding rates are certain state-dependent variables, such as how long it takes, and what kind of transient stresses are produced, in response to a change in sliding rate. Other characteristics of the rock can be determined in ‘slide-hold-slide’ experiments in which sliding is periodically stopped for various lengths of time and then restarted at the same sliding rate. The surfaces have a chance to “heal” or recover strength during the hold times as the points of contact between the sliding surfaces creep and evolve.

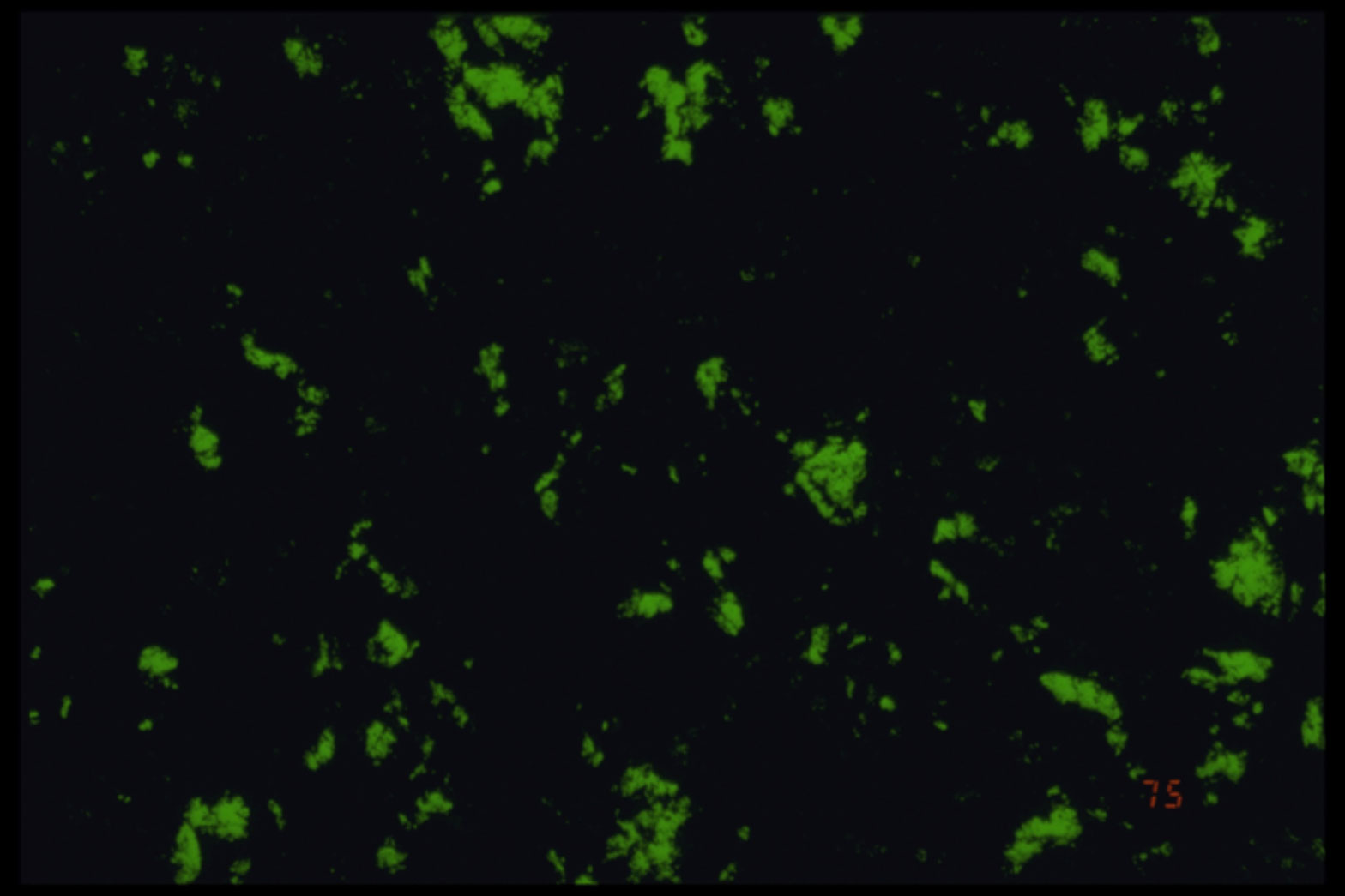

In this experiment, roughened clear plastic plates are pressed against one another, simulating the contact surface along the two sides of a fault plane. The plates only touch where the high spots on each surface (asperities) are in contact. Light transmits through these points of contact (green areas). Light is scattered across sections of the plates that are not in contact (black areas). As the plastic plates are sheared passed one another, the green areas will migrate, coalesce or disappear with time in the same way that rock surfaces evolve during frictional shearing.