History of the Rock Physics Laboratories

On March 27, 1964 the second largest earthquake in recorded history, with a magnitude of 9.2, occurred under Prince William Sound near the coast of Alaska, as the Pacific crustal plate rapidly slid under the North American plate. The violent shaking and tsunami that ensued destroyed much of the city of Anchorage and many nearby villages. The severity of the earthquake prompted the United States Geologic Survey to establish the National Center for Earthquake Research (NCER) in Menlo Park, California in 1965, building on its substantial capabilities in earthquake geology and crustal studies. At the same time the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) predecessor organization established the Earthquake Mechanism Laboratory in San Francisco to augment its role in seismic observatory operations. In 1973 the NOAA earthquake programs were moved to the USGS and the new Office of Earthquake Studies was established to bring together seismologists and geologists. This center has evolved since its early conception into the current Earthquake Science Center in Menlo Park, with field offices in Pasadena and Seattle. Other centers with earthquake programs within the USGS are located in Golden, Colorado and Reston, Virginia.

Less than a decade after the Alaska earthquake, California’s 1971 San Fernando earthquake also caused significant damage and loss of life. This destructive earthquake provided additional impetus for the United States Congress to establish the National Earthquake Hazards Reduction Program (NEHRP) in 1977 to coordinate funding and emergency response across a variety of federal agencies. Many of these agencies have evolved or merged over the years, and today NEHRP oversees earthquake programs within the USGS, the National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

The Laboratories

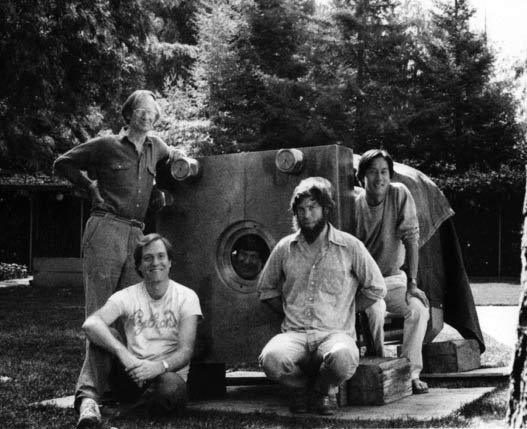

As part of the Earthquake Science Center, the Rock Physics Laboratories have been world leaders in studying the physical processes that control earthquakes for more than 45 years. In the early years of the NCER program, it was recognized that basic research into the physics of earthquakes would be necessary. By the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, several geophysicists had been recruited to establish research laboratories at the USGS campus in Menlo Park, California, including James Byerlee, James Dieterich, Stephen Kirby, Lou Paselnik and others. Each developed innovative laboratory apparatus and research programs to investigate different aspects of earthquake behavior.

James Byerlee designed and built several triaxial rock deformation machines to study brittle rock behavior at high pressure and temperatures, simulating the conditions where earthquakes are generated in the earth’s crust. His research focused on the strength and frictional behavior of rocks, and in particular the “stick-slip” phenomenon of sliding rocks surfaces, where the building up and sudden release of energy is analogous to the earthquake process. His legacy includes the well known Byerlee’s Law, describing the coefficient of friction of most geologic materials as a function of stress.

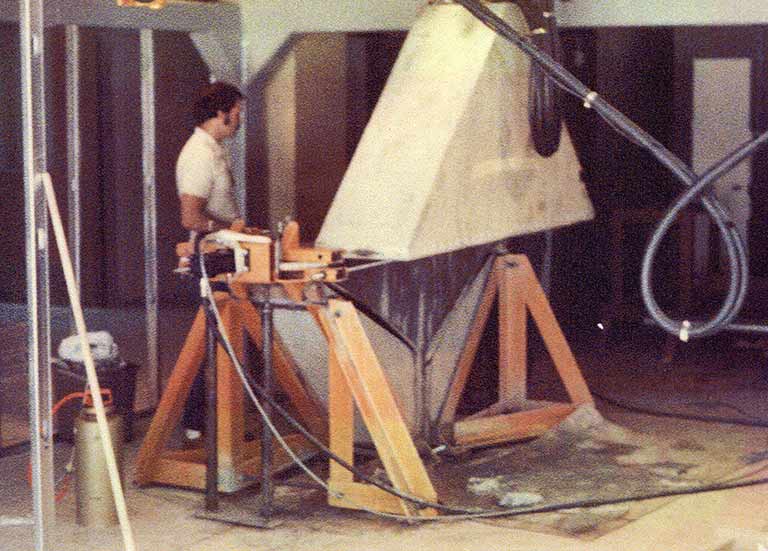

James Dieterich addressed the problem of earthquake nucleation and propagating by developing a large-scale biaxial press containing a 1.5 meter square rock with a 2 meter fault running diagonally from corner to corner. The fault is instrumented with an array of slip sensors and strain gages that measure local slip and stress changes at many locations along its length. This unique earthquake-generating machine is large enough to allow both nucleation and rupture propagation to occur on the fault surface. In this way, the slow earthquake initiation process can be studied in detail, as well as the way that the rupture propagates along the fault and ultimately stops. This apparatus, together with a smaller double-direct shearing machine, were used to establish the important rate- and state-dependent friction equations that are used to describe time-dependent processes of earthquake nucleation and occurrence.

Stephen Kirby focused on upper mantle processes and deep, subduction-zone earthquakes using a “Griggs Rig” apparatus, originally developed at UCLA, and other deformation apparatus custom-built at the USGS. His work included a systematic study of the abundant mantle mineral olivine, leading to a new understanding of deep-focus earthquakes. A key contribution was the discovery and characterization of “transformational faulting”, a shear instability triggered by phase transformations of minerals as they are dragged down into the earth’s mantle as part of subducting crustal plates.

Lou Peselnick and Hsi-Ping Liu designed apparatus to study the attenuation of seismic waves through geologic material at elevated pressures and temperatures. Attenuation is often expressed in terms of the Seismic Quality Factor, or “Q”, and is important for interpreting seismic velocity data. Their pioneering work confirmed the frequency independence of Q, and enabled seismologists to understand seismic body waves and surface waves in a consistent way.

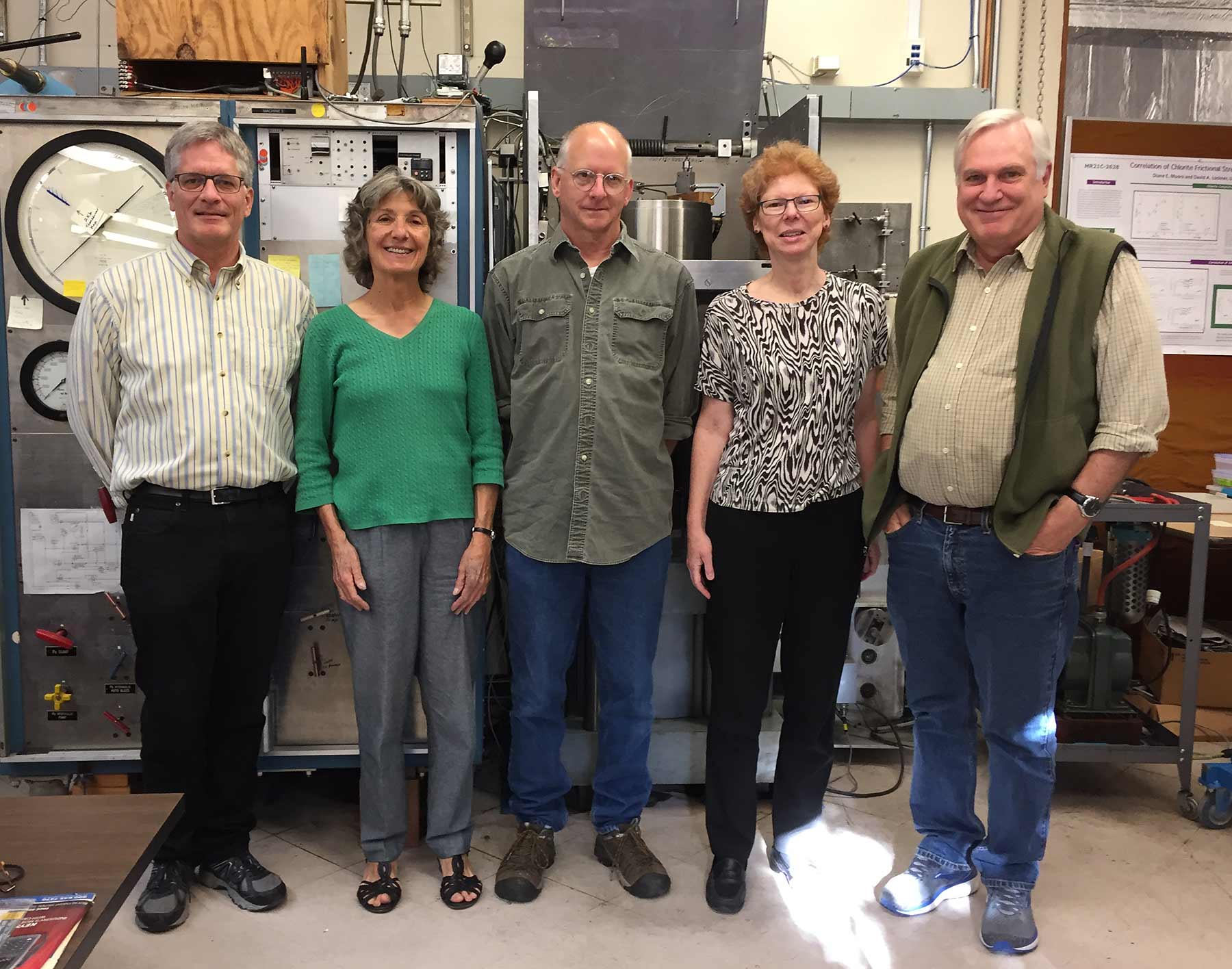

From their inception in the late 1960’s, these laboratories have evolved as new people contribute to the study of earthquakes, including numerous students, post-doctoral researchers and visiting scientists. Presently the laboratory started by James Byerlee contains five triaxial machines for high-temperature, high-pressure experiments, and a rotary–shear machine, on which large-displacement, high-speed experiments can be conducted. Besides the study of earthquakes, the experimental techniques developed in this laboratory have also been applied to problems of petroleum reservoir engineering, nuclear waste disposal, and geothermal energy extraction. The lab currently includes researchers David Lockner (head), Diane Moore, Carolyn Morrow and Nick Beeler. The 2-meter press and double-direct shearing machine developed by James Dieterich are operated today by Brian Kilgore and Nick Beeler and continue to be used to study earthquake nucleation and rupture. Steve Kirby’s interest in Earth materials extended to planetary ices and gas hydrates, resulting in much of the original lab being restructured for low-temperature experimental studies. The laboratory is now run by Laura Stern.

Gas Hydrates Lab

Gas hydrates are a significant potential energy source occurring in ocean-floor sediments at water depths greater than 500 meters and beneath Arctic permafrost. The USGS operates a gas hydrates laboratory on its Menlo Park campus. This video features USGS geophysicists Laura Stern and Steve Kirby who relate details on how they study and create gas hydrates in their super-cooled lab. Work in the lab is funded by the U.S. Department of Energy and by the USGS Gas Hydrates Project.

Current Research Staff

Jump to Navigation

Jump to Navigation