-

Tectonic Plate Boundaries

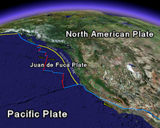

The outermost shell of the Earth consists of a mosaic of rigid “plates” that have been moving relative to one another for hundreds of millions of years. Two of these moving plates meet in western California; the boundary between them is a zone of faults, the principal one being the San Andreas fault. The Pacific Plate (on the west) slides horizontally northwestward relative to the North American Plate (on the east), causing earthquakes along the San Andreas and associated faults. The San Andreas fault is a transform plate boundary, accomodating horizontal relative motions. For more information on the story of plate tectonics see This Dynamic Earth.

Tectonic Plate Boundaries (321 kB)

-

Real-Time Earthquakes

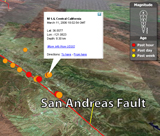

Most earthquakes occur in the upper 10-12 miles (15-20 km) of the Earth’s crust as the result of failure on faults caused by the strains induced by plate motions. The word “earthquake” is used to describe both sudden slip on a fault and the resulting ground shaking. Earthquakes are also associated with active volcanism and the flow of magma at depth. California is also one of the few places in the world where faults “creep”, that is, the fault slip is slow and continuous and occurs aseismically, which is to say that this slip does not occur as the result of an earthquake. You may be surprised to learn that 500,000 detectable earthquakes occur globally each year. Of those, nearly 100,000 can be felt, and 100 cause damage. The following file records earthquake activity around the world for the past week. Notice how the location of earthquakes are concentrated along the plate boundaries of the Earth. Earthquakes in the Bay Area reflect the relative motion of the Pacific and North America plates.

-

Plate Boundary Ruptures Along Western North America

In addition to the 1906 rupture of the San Andreas fault in northern California, the San Andreas fault in south-central California also experienced a similar size earthquake in 1857, rupturing the San Andreas fault from Parkfield to just northwest of San Bernardino. A 112-mile (180 km) long creeping section exists on the central portion of the San Andreas between the 1857 and 1906 ruptures. The San Andreas fault southeast of San Bernardino has not experienced a major earthquake in the historical record, and paleoseismic investigations of this reach of the fault suggests it last ruptured in the late 17th Century. North of Cape Mendocino, the San Andreas fault merges with the plate boundary of the Cascadia subduction zone that lies offshore of northernmost California, Oregon, and Washington. We know from paleoseismic investigations in Washington and Oregon and tsunami records in Japan, a magnitude 9 earthquake ruptured the Cascadia subduction zone in 1700. Although many Bay Area residents remember the 1989 Loma Prieta as the "big one", it pales in comparison to these earlier fault ruptures.

Jump to Navigation

Jump to Navigation