Image: Sara Boore, USGS

The Recording

A recording was done on February 15, 2000 at the Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics with the musicians from the premiere. Patricio de la Cuadra was the recording engineer. It is presented here in mp3 format. The earthquake sounds include a lot of bass, so if you don't have good speakers on your computer please try using headphones.

Why did I write the quartet?

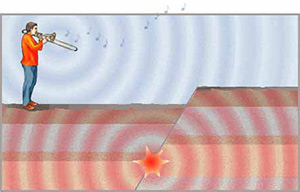

Earthquake Quartet #1 is an outgrowth of a lecture that I have been giving since 1997. This lecture, "The Music of Earthquakes," mixes performance and lecture, music and science, acoustic instruments and computer generated sounds. A musician controls the source of the sound and the path it travels through their instrument in order to make sound waves that we hear as music. An earthquake is the source of waves that travel along a path through the earth until reaching us as shaking. It is almost as if the earth is a musician and people, including seismologists, are the audience who must try to understand what the music means. By listening to both music and the audio playbacks of the earth shaking, we explore this analogy and find new ways to learn about the earth, earthquakes, musical instruments and music. This lecture has been a popular feature at the USGS in Menlo Park, several Universities, schools, and was an invited presentation at symposiums on science and art organized by both the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the scientific research society Sigma Xi.

At several of the early lecture presentations, audience members asked if I thought about using the audio playbacks of the seismograms as elements in a piece of music. These sounds are rather percussive and so I decided to compose a quartet for trombone, cello, voice and seismograms. The instrumentation was chosen because the lecture includes those three instruments.

What is the quartet trying to say?

Earthquake Quartet #1 is a concept piece that starts by describing the earthquake cycle in which plate motions build up strain until it is suddenly released during earthquakes. The latter part of the piece is based on the idea that society and culture, including music, takes place with the earthquakes as an often ignored backdrop. However, the geologic processes are an instrinsic part of our existence and ignoring them can have its consequences. Listeners may recognize that one theme from the second section is a rhythmically distorted quote from the Allemande of Bach's second "Suite for Unaccompanied Cello" which is then further inverted and modified.

How do we hear shaking?

When a loudspeaker produces sound it shakes. During an earthquake the ground shakes and that is recorded as a seismogram. To convert the earthquake shaking to sound the loudspeaker must shake the same way the ground did. But, if it really did that the pitch would be too low for people to hear. If the speed at which the loudspeaker moves back and forth is increased to be much faster than the ground actually moved, then we can hear it. This is easy to do because both seismograms and audio are stored in computer files as a series of numbers or samples. The seismograms used in this piece were recorded with 100 samples per second. When I converted the seismogram files to audio files, I simply lied to the conversion program and said there were 8000 samples per second. That means the seismograms used in this piece were sped up by a factor of 80 which increases their pitch by 6 octaves plus 1 and a half steps. You can use a piano or keyboard to hear how different two notes that far apart sound. But you will need a full size one because many small keyboards don't cover a 6 octave range. And there are few other instruments capable of covering that large a range and no ones voice can do it. Note that with the pitch 80 times higher the duration of the seismogram becomes 80 times shorter. So what you hear is much shorter than the shaking that took place during these earthquakes.

During the performance of the piece, the audio is played back through loudspeakers driven either by a computer or by a CD player.

The earthquakes are:

- the 1992 magnitude 7.3 Landers earthquake in southern California as recorded at Parkfield, California This is the large rumble heard near the beginning.

- two recordings of a magnitude 2 earthquake at Parkfield and recorded at Parkfield on two different stations (beats 1 and 3).

- two recordings of a magnitude 5.1 earthquake at Parkfield recorded at both Parkfield (beat 2) and at Hollister, California (beat 4). Note that the fourth beat is the slower moving S wave while the pickup to the fourth beat is the faster moving P wave.

Performers and Performance History

This two minute piece was composed during November and December, 1999 and had its premiere at a presentation of "The Music of Earthquakes" on December 16 at Moscone Hall in San Francisco as part of the annual Fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union. The musicians at the premiere were:

- Soprano and USGS Geophysicist Stephanie Ross

- Cellist and Stanford University Geophysics Graduate Student David Schaff (now at Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory)

- Trombonist and USGS Geophysicist Andrew Michael

Since then, it has been performed many times as part of the Music of Earthquakes lecture and for other earthquake-related events such as the PIEQF shake table installation and the recording has been played on a variety radio programs around the world.

Related Links

- News Stories about the Earthquake Quartet: CNN, Associated Press/San Mateo County Times

- Listen to Earthquakes: Learn about seismology by listening to seismograms

- PIEQF Installation and Parkfield research

Jump to Navigation

Jump to Navigation